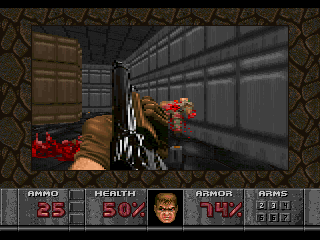

Meet Doom, Doom and Doom. The first image on the top left is Doom on the 32X. The top right shows Doom on the Jaguar, and the bottom left is the SNES. Note: They are displayed in release order.

Having completed the SNES Doom, I'd like to address some insights to the modding community. You may wonder what relevance any of this has to you. Certainly, there are some wonderful mods out there based on the console versions of Doom--there are total conversions of Doom for SNES, 32X, Jaguar, Playstation, N64 and even GBA. There's a massive level set comprised of the edited levels from every 90s system but the SNES, with a few Doom 64 levels stuck in for good measure. A few people have even ripped "No Rest for the Living", the exclusive new episode created for Doom's re-release on the XBOX 360 and PS3.

These are all beautiful creations and/or adaptations, and they've contributed to the non-canon canon of the fan-based evolution of the game. The PC is the tool that has allowed the most innovation for those who want to see Doom reach its full potential without perversion by Doom 3, or whatever Doom 4 is going to look like. I no longer look to Id Software for the next big thing when it comes to this incredible game. I look to console ports and I look to modders.

The modders missed a few details when they made these conversions, but I don't hold it against them. Hell, I could never accomplish what they did. It's not my forte. I'm lucky if I can make a single map without getting so frustrated that I beat on the desk. The point is that the best way to learn about the console games is to actually play them. It's one thing to rip the resources and port them to the PC, it's another to experience how they worked, their distinctions and drawbacks, the feel of the controllers and the functioning of the original hardware. These are all ways of learning the ways that the game can be different every time you play it. They can inspire creativity. They can show how minds other than those at Id innovated to compensate for their consoles' lack of power, and how minds at Id innovated to make use of the things certain consoles could do better. On the Playstation, one example would be the Nightmare Spectre. On the SNES, I could point to improved invisibility or upgraded music. On the Jaguar, I could talk about the improved lighting effects. Need I go on...?

John Carmack had this to say about programming on the Jag: "The quick recap on the jaguar:

The memory, bus, blitter and video processor were 64 bits wide, but the processors (68k and two custom risc processors) were 32 bit.

The blitter could do basic texture mapping of horizontal and vertical spans, but because there wasn't any caching involved, every pixel caused two ram page misses and only used 1/4 of the 64 bit bus. Two 64 bit buffers would have easily trippled texture mapping performance. Unfortunate.

It could make better use of the 64 bit bus with Z buffered, shaded triangles, but that didn't make for compelling games.

It offered a useful color space option that allowed you to do lighting effects based on a single channel, instead of RGB.

The video compositing engine was the most innovative part of the console. All of the characters in Wolf3D were done with just the back end scalar instead of blitting. Still, the experience with the limitations and hard failure cases of that gave me good amunition to rail against microsoft's (thankfully aborted) talisman project.

The little risc engines were decent processors. I was surprised that they didn't use off the shelf designs, but they basically worked ok. They had some design hazards (write after write) that didn't get fixed, but the only thing truly wrong with them was that they had scratchpad memory instead of caches, and couldn't execute code from main memory. I had to chunk the DOOM renderer into nine sequentially loaded overlays to get it working (with hindsight, I would have done it differently in about three...).

The 68k was slow. This was the primary problem of the system. You options were either taking it easy, running everything on the 68k, and going slow, or sweating over lots of overlayed parallel asm chunks to make something go fast on the risc processors.

That is why playstation kicked so much ass for development -- it was programmed like a single serial processor with a single fast accelerator.

If the jaguar had dumped the 68k and offered a dynamic cache on the risc processors and had a tiny bit of buffering on the blitter, it could have put up a reasonable fight against Sony."

So I've completed SNES Doom, and I think it's time to compile a final list of things it does not have (though some will probably admittedly occur to me in later posts as I discuss experiences on other consoles and wish to make comparisons). I've talked up its finer points, but now it's time to show the limitations of a 16-bit system.

Corpses are not turned into puddles when doors close on them. They just stay as they are. No enemies are gibbed by explosions--they all have one death animation. You'll see random gibbed bodies here and there, however. Lining up punches is a little hard, so that you'll probably get bitten by Pinkies before you manage to hit them (I believe this is referred to as "hitscan"?). All items make the same sound when you pick them up, so there's no special sound for Soul Spheres, etc. Dropped enemy weapons are not displayed as sprites. They're effectively invisible.

There are other idiosyncrasies which I don't think I've touched on, so here they are: You can pick up a weapon even if you don't need ammo--it's effectively wasted. Explosions seem to have a greater range and are almost always deadly for the player. When I faced the Cyberdemon in Warrens, I killed him with only six or seven rockets. All the big enemies are much easier to kill, which is actually great. I always think I'm going to die when they pop up! Also, enemies attack immediately. There's almost no delay between their alert sound and their first volley. So if you open the door on a Baron, you'd better move your ass ASAP!

SNES Doom is such an anomaly, but once you've been playing it for a while, it's actually exciting. What can I say? I love a challenge. Williams Entertainment didn't create it, but they published it, and I can't help but think that it had some kind of influence on the creation of Playstation Doom. We'll get to that when I start said Doom. SNES Doom was the first to feature strafing via the shoulder buttons, though it excluded circle-strafing. It was the first to feature a translucent invisibility effect instead of shimmering pixels. These featured carried into other ports, though on other ports the translucent invisibility may have been created using a different programming technique. It should be noted, however, that Heretic may also have been the inspiration for this form of partial invisibility, as it featured the same effect and was released first.

I'm going to be playing Playstation Doom next. I look forward to sharing my insights and the adventure! In the meantime, here's a new timeline:

Doom v1.0: December 10, 1993

Doom v1.1: December 16, 1993

DEU: January 26, 1994

Doom v1.2: February 17, 1994

Origwad: March 7, 1994

Dead Base: April 25, 1994

Doom v1.4: June 28, 1994

Doom v1.5: July 8, 1994

Doom v1.6: August 3, 1994

Doom v.1.666: September 1, 1994

Doom II: September 30, 1994

Doom v1.7: October 11, 1994

Aliens Total Conversion: November 3, 1994

Doom v1.7a: November 8, 1994

32X Doom: November 14, 1994

Jaguar Doom: November 28, 1994

Heretic: December 23, 1994

Doom v1.8: January 23, 1995

Doom v1.9: February 1, 1995

The Ultimate Doom: April 30, 1995

SNES Doom: September 1, 1995

Playstation Doom: November 16, 1995

Master Levels for Doom 2: December 26, 1995

Doom 95: August 20, 1996

These are all beautiful creations and/or adaptations, and they've contributed to the non-canon canon of the fan-based evolution of the game. The PC is the tool that has allowed the most innovation for those who want to see Doom reach its full potential without perversion by Doom 3, or whatever Doom 4 is going to look like. I no longer look to Id Software for the next big thing when it comes to this incredible game. I look to console ports and I look to modders.

The modders missed a few details when they made these conversions, but I don't hold it against them. Hell, I could never accomplish what they did. It's not my forte. I'm lucky if I can make a single map without getting so frustrated that I beat on the desk. The point is that the best way to learn about the console games is to actually play them. It's one thing to rip the resources and port them to the PC, it's another to experience how they worked, their distinctions and drawbacks, the feel of the controllers and the functioning of the original hardware. These are all ways of learning the ways that the game can be different every time you play it. They can inspire creativity. They can show how minds other than those at Id innovated to compensate for their consoles' lack of power, and how minds at Id innovated to make use of the things certain consoles could do better. On the Playstation, one example would be the Nightmare Spectre. On the SNES, I could point to improved invisibility or upgraded music. On the Jaguar, I could talk about the improved lighting effects. Need I go on...?

John Carmack had this to say about programming on the Jag: "The quick recap on the jaguar:

The memory, bus, blitter and video processor were 64 bits wide, but the processors (68k and two custom risc processors) were 32 bit.

The blitter could do basic texture mapping of horizontal and vertical spans, but because there wasn't any caching involved, every pixel caused two ram page misses and only used 1/4 of the 64 bit bus. Two 64 bit buffers would have easily trippled texture mapping performance. Unfortunate.

It could make better use of the 64 bit bus with Z buffered, shaded triangles, but that didn't make for compelling games.

It offered a useful color space option that allowed you to do lighting effects based on a single channel, instead of RGB.

The video compositing engine was the most innovative part of the console. All of the characters in Wolf3D were done with just the back end scalar instead of blitting. Still, the experience with the limitations and hard failure cases of that gave me good amunition to rail against microsoft's (thankfully aborted) talisman project.

The little risc engines were decent processors. I was surprised that they didn't use off the shelf designs, but they basically worked ok. They had some design hazards (write after write) that didn't get fixed, but the only thing truly wrong with them was that they had scratchpad memory instead of caches, and couldn't execute code from main memory. I had to chunk the DOOM renderer into nine sequentially loaded overlays to get it working (with hindsight, I would have done it differently in about three...).

The 68k was slow. This was the primary problem of the system. You options were either taking it easy, running everything on the 68k, and going slow, or sweating over lots of overlayed parallel asm chunks to make something go fast on the risc processors.

That is why playstation kicked so much ass for development -- it was programmed like a single serial processor with a single fast accelerator.

If the jaguar had dumped the 68k and offered a dynamic cache on the risc processors and had a tiny bit of buffering on the blitter, it could have put up a reasonable fight against Sony."

So I've completed SNES Doom, and I think it's time to compile a final list of things it does not have (though some will probably admittedly occur to me in later posts as I discuss experiences on other consoles and wish to make comparisons). I've talked up its finer points, but now it's time to show the limitations of a 16-bit system.

Corpses are not turned into puddles when doors close on them. They just stay as they are. No enemies are gibbed by explosions--they all have one death animation. You'll see random gibbed bodies here and there, however. Lining up punches is a little hard, so that you'll probably get bitten by Pinkies before you manage to hit them (I believe this is referred to as "hitscan"?). All items make the same sound when you pick them up, so there's no special sound for Soul Spheres, etc. Dropped enemy weapons are not displayed as sprites. They're effectively invisible.

There are other idiosyncrasies which I don't think I've touched on, so here they are: You can pick up a weapon even if you don't need ammo--it's effectively wasted. Explosions seem to have a greater range and are almost always deadly for the player. When I faced the Cyberdemon in Warrens, I killed him with only six or seven rockets. All the big enemies are much easier to kill, which is actually great. I always think I'm going to die when they pop up! Also, enemies attack immediately. There's almost no delay between their alert sound and their first volley. So if you open the door on a Baron, you'd better move your ass ASAP!

SNES Doom is such an anomaly, but once you've been playing it for a while, it's actually exciting. What can I say? I love a challenge. Williams Entertainment didn't create it, but they published it, and I can't help but think that it had some kind of influence on the creation of Playstation Doom. We'll get to that when I start said Doom. SNES Doom was the first to feature strafing via the shoulder buttons, though it excluded circle-strafing. It was the first to feature a translucent invisibility effect instead of shimmering pixels. These featured carried into other ports, though on other ports the translucent invisibility may have been created using a different programming technique. It should be noted, however, that Heretic may also have been the inspiration for this form of partial invisibility, as it featured the same effect and was released first.

I'm going to be playing Playstation Doom next. I look forward to sharing my insights and the adventure! In the meantime, here's a new timeline:

Doom v1.0: December 10, 1993

Doom v1.1: December 16, 1993

DEU: January 26, 1994

Doom v1.2: February 17, 1994

Origwad: March 7, 1994

Dead Base: April 25, 1994

Doom v1.4: June 28, 1994

Doom v1.5: July 8, 1994

Doom v1.6: August 3, 1994

Doom v.1.666: September 1, 1994

Doom II: September 30, 1994

Doom v1.7: October 11, 1994

Aliens Total Conversion: November 3, 1994

Doom v1.7a: November 8, 1994

32X Doom: November 14, 1994

Jaguar Doom: November 28, 1994

Heretic: December 23, 1994

Doom v1.8: January 23, 1995

Doom v1.9: February 1, 1995

The Ultimate Doom: April 30, 1995

SNES Doom: September 1, 1995

Playstation Doom: November 16, 1995

Master Levels for Doom 2: December 26, 1995

Doom 95: August 20, 1996